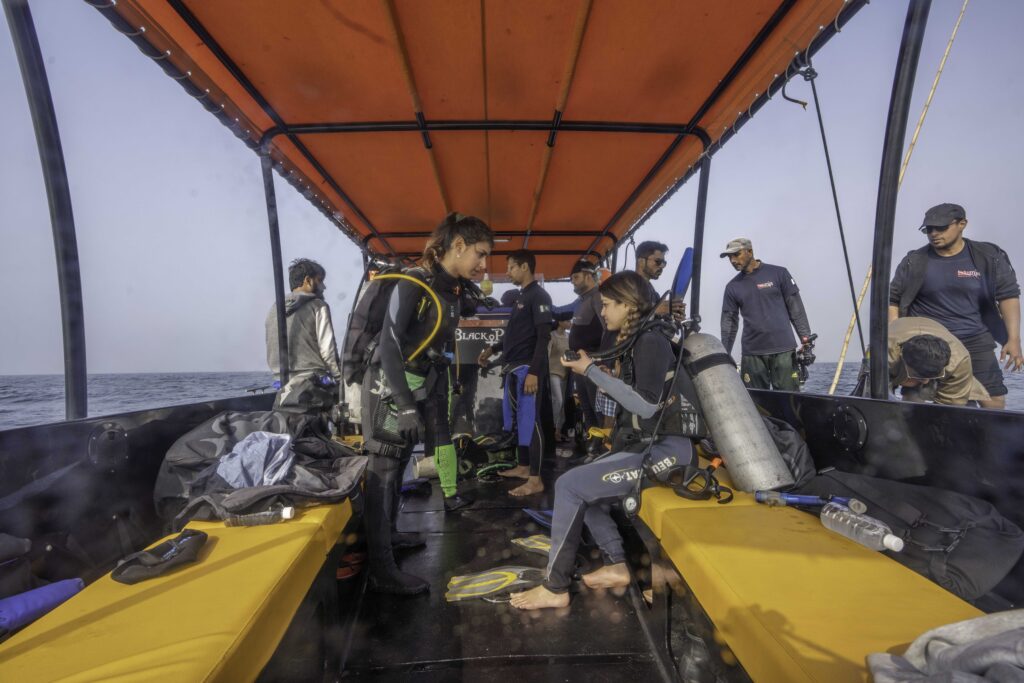

By Nadia Aswani, Marine Zoologist and Padi instructor, Photos by Alfred Minnaar

I swam through the water, my hands and arms becoming more and more wrapped up with each movement. Constricted. Weighed down by layers of plastic. Bags, wrappers, sheets, toys, clothes, bottles, all jumbled together drifting along with me. Even though I knew my pockets were already full I scooped up more, tucking them into my belt, into the arm holes of my dive jacket, handing some to the divers behind me, but we remained surrounded. Our efforts didn’t seem to be making a difference but I stubbornly kept plucking as many bits as I could carry. I looked up at the graceful and majestic manta ray circling above us, plastic wrapped around her tail, bending it slightly with the added weight, and hoped it was a sight I’d never have to see again.

While studying marine biology at university, the issues of marine habitat degradation and climate change pervaded my entire educational experience, coloring every topic, and since then plastic pollution and ghost fishing gear have shrouded my career as a dive instructor. Now, as I’m entering into the world of science communication and filmmaking, I hope to be able to bring people’s attention to these subjects in a way that enables them to actively participate in positive environmental practices around the world. But you may ask HOW can we as individuals address environmental problems that are on such a large scale?

I believe that solutions as simple as making small changes in our daily practices, if followed en masse, can make significant changes when it comes to protecting our oceans and beaches. This winter I discovered Trshbg to be one such solution. In January I travelled to my home country of Pakistan, a place rife with pollution, grey and brown waters and plastic in almost every corner of the sea-bed, for a diving trip, and I was gifted several Trshbg hip and calf bags to try out during my underwater excursions. Preparing for our fun dives off the coast of Karachi, Sindh, home to one of the biggest and busiest fishing and trading ports in South Asia, myself and each of our cohort fastened on our Trshbgs for the first time. Made of recycled materials, except for the little clip, the mesh bags mirror the natural shape of your thigh and calf, and strap directly on, so as not to create any resistance while swimming. Certain we would come across plenty of scrap, it was more than easy to stuff plastic and trash of all shapes into the bags, with a small funnel in the mouth of the bag helping us push it in. The funnel also prevented the rubbish from being washed back out again. The bags being brightly coloured and easily identifiable was also helpful as one of the dive guides swam over to me and popped a sweet wrapper into mine; by the end of our two dives everyone had filled their bags to the brim. Once we were back on the boat it was more than easy to dump everything out using the additional zip that runs the length of the bag.

Trshbgs are certainly a clever solution; their ingenious design allowed us to collect and tuck away trash quickly without it becoming an impediment to our diving activities. This proved even truer when using them on a ghost gear recovery dive, with the Olive Ridley Project (ORP), Pakistan. I began volunteering with the ORP, a charity dedicated to alleviating and removing abandoned and harmful fishing gear from the ocean, in early 2017. During the trip myself and my South African travelling companion accompanied the ORP’s net recovery team to try to find and bring up a 180sq/m net that was entangled around several rocks, just offshore.

Our comrades, ORP Field Coordinator Asif Baloch and Marine Archaeologist Amer Khan both strapped Trshbgs on, alongside their usual dive gear. As someone who generally doesn’t like to dive with gloves on, my bag was also a handy place to store my diving gloves before I needed to put them on for the net extraction activities. The hands-free nature of the Trshbgs allowed us to pick up and stuff smaller bits of rubbish into the bags while focusing our main attentions on the nets, and as we cut and pulled the net apart we were even able to capture and tuck away the smaller bits of plastic and nylon peeling of the net, that would have otherwise drifted away.

As someone who often dives in waters where plastic pollution is rampant, the Trshbg makes a huge difference to my overall diving experience. I dive with an open-harness, minimalistic travel-style BCD, which has no pockets at all, and I constantly struggle to find a place to put trash when I find it. If I’m teaching a diving course, then having my hands free is very important, and holding things isn’t an option, the same is true if I’m conducting a survey and need to be holding scientific tools. Often if I’m teaching or doing research, much of the waste I see I have to leave behind, but wearing a Trshbg on my dives could change that.

The question that’s been going around my head since the trip is: can the act of strapping on a Trshbg change a person’s habits? Are divers and surfers more likely to pick up trash if they have a specific place to put it?

I believe the answer is yes, that our human brains are efficient, and like to form habits, freeing up mental resources for other tasks. If we do something frequently enough, it becomes automatic, like putting on a seatbelt as soon as you get into the car. Picking up trash can too become a habit, and the key to altering the behavior of the world’s ocean visitors could lie in making the Trshbg a staple for every diver and surfer, in every dive shop, on every coast, in every country. Something as vital to your dive gear as your regulator or LPI, so you begin to use it without even thinking.

Picking up trash could become second nature to us. If we consider the difference this could make if practiced by the 6 million active divers, the 20 million snorkelers and the 35 million surfers in the world today, the possibilities are endless, and the impacts of using Trshbg could be extraordinary.

Writer Bio – Nadia Aswani is a Pakistani Marine Zoologist and PADI Instructor passionate about ocean conservation. Having worked as a marine researcher and in the dive industry for several years she is now turning to science communication as the future of conservation. She’s currently completing her masters in Wildlife Filmmaking in the UK, and hopes to join the extraordinary cadre of men and women, telling the stories of our oceans, with the hope of preserving them for future generations.

All photos by Alfred Minnaar